This is the story of our coastal places. Most of Scotland borders the sea, its coast a ribbon more than 10,000 miles long that defines our enduring relationship with the oceans. It is where we are most aware of extremes of weather, the balmiest of seaside days and the relentless battering of icy storms. For thousands of years, people lived mostly on the coast in order to survive and, still today, well over half the Scottish population live near the sea.

The coast is our place of departure and arrival, the last point of contact with home for explorers and adventurers and the promise of safe harbour for sailors and fishermen. The sea has been the source of Scotland’s fortunes, from fishing the abundance of its waters to sailing trade routes to do business with far-off lands. Some of the biggest ships of their day were built on the west coast and great quantities of oil and natural gas have been extracted from under its northern waters. Now we are leading the world with developments in wind and tidal power to provide us with clean, renewable energy.

Exposed to the elements, coastal settlements have had to be physically resilient but even the most stoical have been vulnerable to changing times and periodic invasions. Many are now reinventing themselves for 21st century holidaymakers, whether they come to drive the North Coast 500, surf, island-hop, enjoy our thriving food culture and unique coastal heritage or simply to experience the restorative power of time spent by the sea.

Iona Abbey, Iona, Argyll and Bute, 1976

Christian missionaries started making the perilous trip across the sea to Scotland from Ireland in the 5th century. The best known of these was St Columba, who came to Iona in 563 and founded a monastic settlement. As the community grew, it produced illuminated manuscripts and accumulated religious treasures which proved irresistible to Viking raiders.

Around 1203, a Benedictine abbey and Augustinian nunnery were built over St Columba’s abbey only to be abandoned when the communities were disbanded during the Scottish Reformation. In 1938, the abbey was rebuilt to house the ecumenical Christian community that remains active on the island today.

Sailing from Brodick, Argyll and Bute, c.1905

Sailing for pleasure has been a feature of Scotland’s coast, especially in the west, since the 19th century.

At first, yachts were large and expensive to build and maintain so this was a pastime for only the wealthiest members of society.

Here Mrs Hoggenheim, of London’s exclusive Park Lane, takes the helm of her friends’ yacht, the Gadfly, when visiting them for the summer on the west coast.

Creagorry, Benbecula, Western Isles, c.1910

The unpredictability of the sea has been an ongoing challenge for those living on Scotland’s islands. Aside from food and shelter, communicating with the mainland and beyond can be problematic in stormy weather.

Island communities such as Benbecula made use of technology as soon as they could to help improve communications by housing a Telegraph Office in one of the island’s traditional buildings.

It was from Benbecula that Flora MacDonald rowed Bonnie Prince Charlie to safety, as immortalised in the famous ‘Skye Boat Song’, when he had been forced to land here during a storm after the Battle of Culloden in 1746.

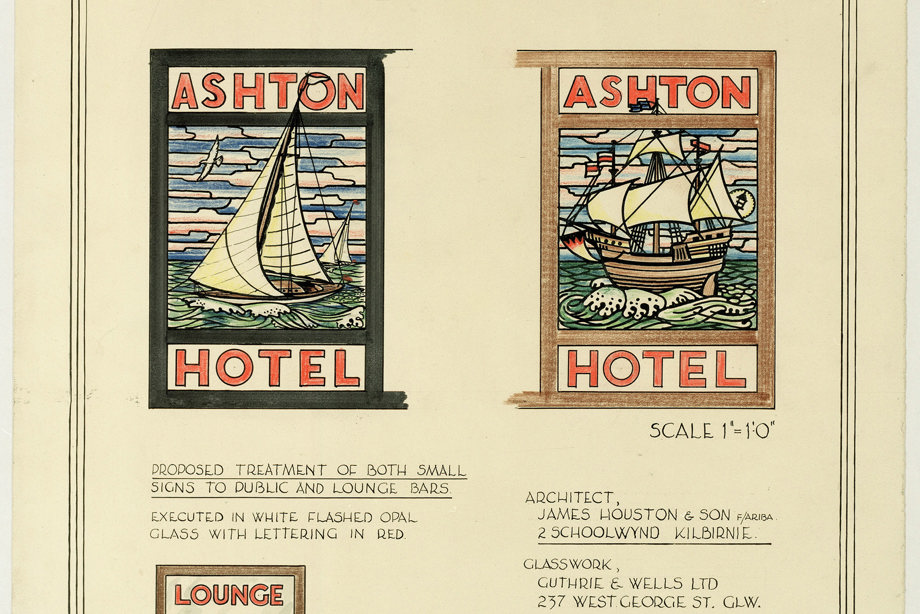

Illuminated signage for the Ashton Hotel, Gourock, Inverclyde, 1958

Buildings for coastal resorts are often designed to reflect their maritime setting. Architect James Houston was a master at providing imaginative concepts for buildings to enhance seaside towns on the west coast.

For a refit of the Ashton Hotel on the seafront at Gourock he installed a Davy Jones’ Locker bar and commissioned the Lion Foundry Co. Ltd, Kirkintilloch, to provide eye-catching illuminated signage with a nautical theme for the exterior.

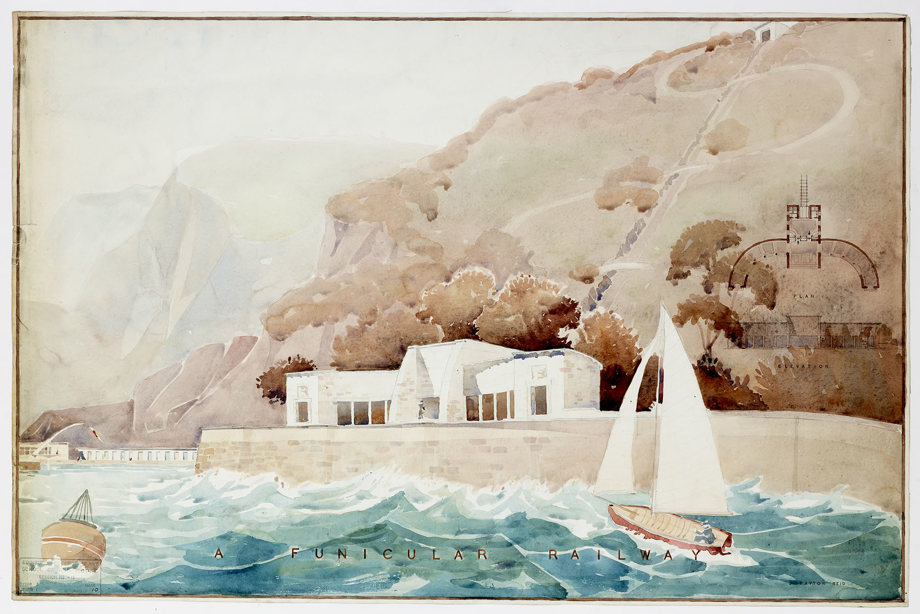

Student design for a funicular railway, c.1940

The business of providing facilities for seaside holidaymakers could be a profitable one. With their future career in mind, student architects of the 1930s were often asked to design buildings for seaside resorts as part of their architectural coursework.

Jean Payton-Reid designed a funicular railway for an imaginary coastline when she was at Edinburgh College of Art.

Seaside holidays, early 1900s

By the turn of the 20th century, going to the seaside for a holiday had become an established tradition for many people.

Cameras had also become more portable, which meant it was possible to capture happy moments such as these women enjoying a dip at Stonehaven or a young girl passing her time on the beach much as children do today.

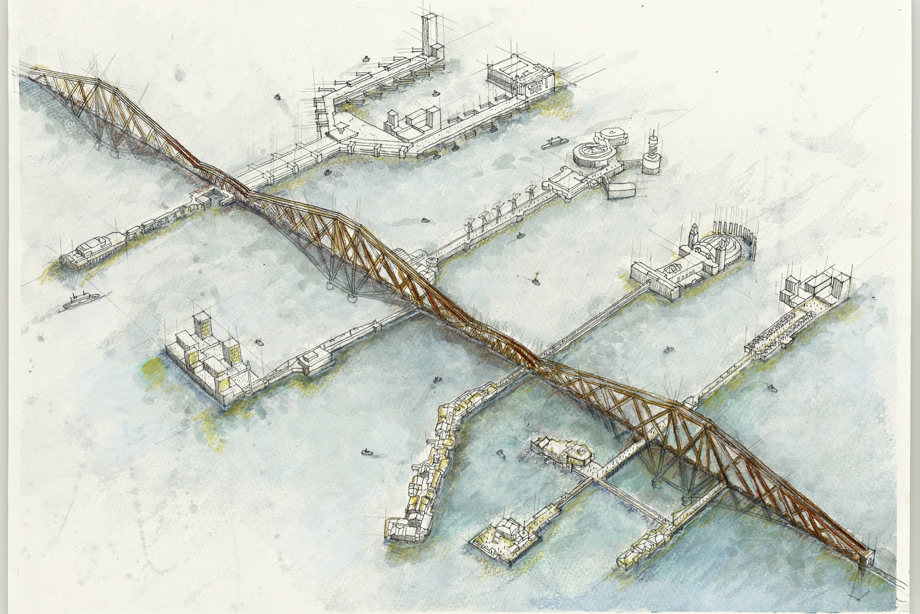

The future?

Throughout history, life in our coastal communities has been shaped by the need to adapt to extremes of weather. We face a new challenge with a predicted rise in sea levels that will require new approaches to living at the land’s edge.

We asked students to imagine ways in which Scotland might build structures to cope with extreme flooding. Wynne McLeish suggested attaching a series of floating piers to the Forth Rail Bridge.

In her futuristic design, energy would be supplied through wind and wave generators to enable a small population living in the piers to thrive in an inhospitable climate.

Scotland's Coast continued

Continue your exploration of Scotland's extraordinary coasts and waters.