Symbol Stone, Pabbay, Outer Hebrides

Beveridge sought out and photographed a number of monuments like this symbol stone in his explorations of Scotland. In his field notes he writes of systematically documenting known monuments in each area he visited, often speaking to local residents to locate them.

While his brazen use of drawing tools to highlight the carvings would not be permitted now due to the possible damage caused, it does demonstrate his eagerness to accurately record these ancient symbols.

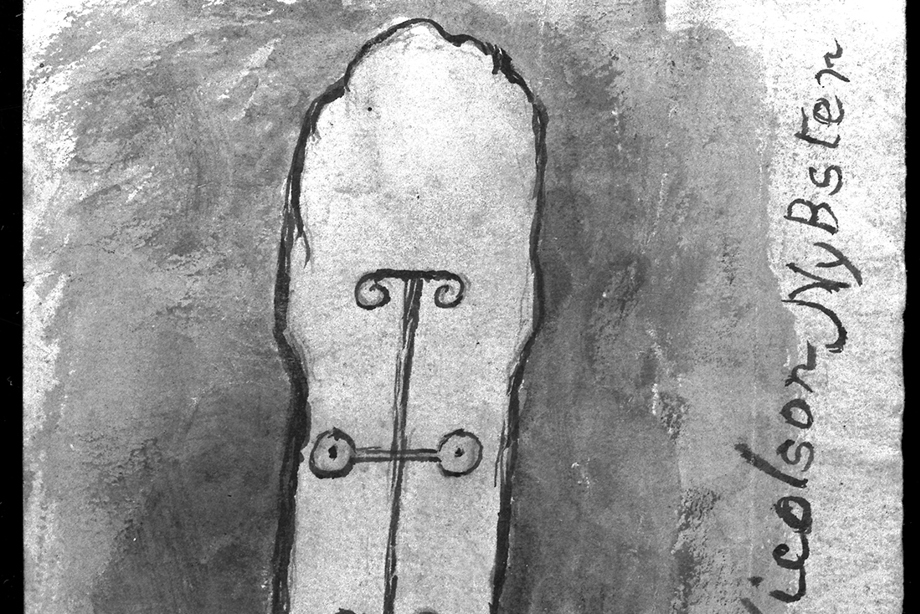

Drawing of cross-slab from Mid Clyth, Caithness

Between 1890 and 1904, Sir Francis Tress Barry excavated a number of sites in Caithness, relying on local people like John Nicolson to help with this work.

Nicolson’s drawing shows an Early Medieval carved stone or cross-slab which still stands in Mid Clyth graveyard in Caithness. While perhaps not as meticulous as some archaeological survey drawings, it artfully provides an atmospheric impression of the slab’s unusual carved design and Nicolson's creative flair.

Fragments of St John's Cross, Iona, Inner Hebrides

Iona is one of the most important religious sites in Scotland, where St Columba formed the first recorded community on the island to teach Christianity.

Beveridge captured these fragments before they were reconstructed and displayed inside the restored Iona Abbey Museum, taking advantage of circumstances to slip unaccompanied into the then derelict Abbey. It is clear from accompanying photographs that he must have turned and rearranged them to capture both faces of the broken fragments.

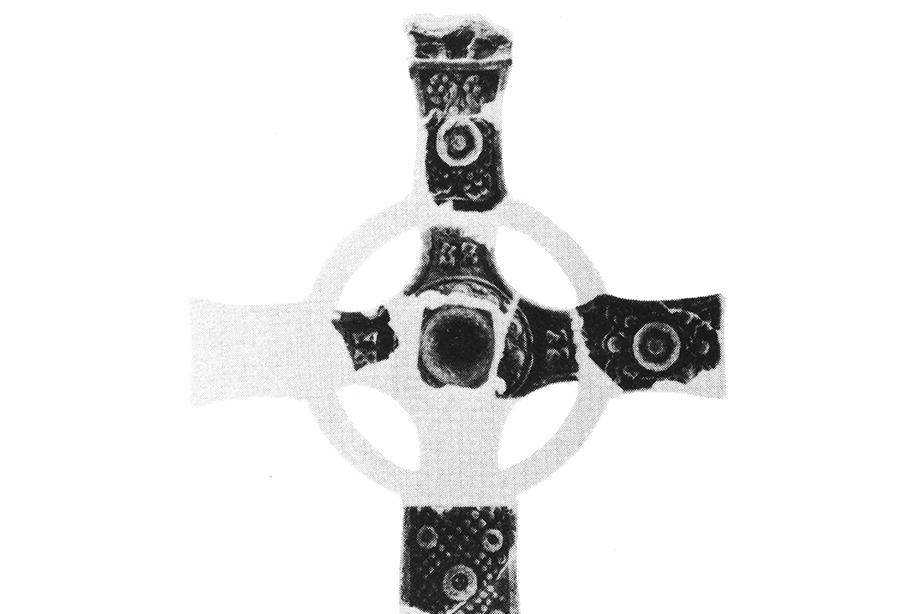

Sketch of St John's Cross, Iona, Inner Hebrides

After St Columba’s death, Iona became a pilgrimage site and crosses like this were used as wayfinders directing visitors to the Abbey. However, the arms of this cross were so long it collapsed almost immediately, and had to be restored many times.

This survey drawing of St John's Cross shows a reconstruction of Beveridge’s fragments before they were restored. Sometimes, when a monument is damaged, a drawing like this might be the only way to visualise its original appearance.

St John's Cross, Iona, Inner Hebrides

In 1927 the pieces were stuck together again, but the intact cross only lasted till 1957. The surviving pieces were brought into the museum, where they now stand restored and preserved.

In 1970 a concrete replica cross was built and stands outside the abbey, creating an interesting debate over authenticity and historical importance. The replica upholds the makers intentions: it is whole and in the original location. However, it cannot portray the passage of time like the original fragments. Which provides a more authentic record of St John’s cross?

Bronze and bone pins and needles, North Uist, Outer Hebrides

These objects were collected on Vallay, North Uist, which is a small coastal island purchased by Beveridge in 1901. This photograph is almost as important as the objects themselves, particularly as they are not currently on public display.

It marks an important part in the life of the objects: when they move out of their original context to become a part of a historical collection. The way Beveridge collected, arranged and documented them gives us insight into Victorian pastimes, values and need to categorise things.

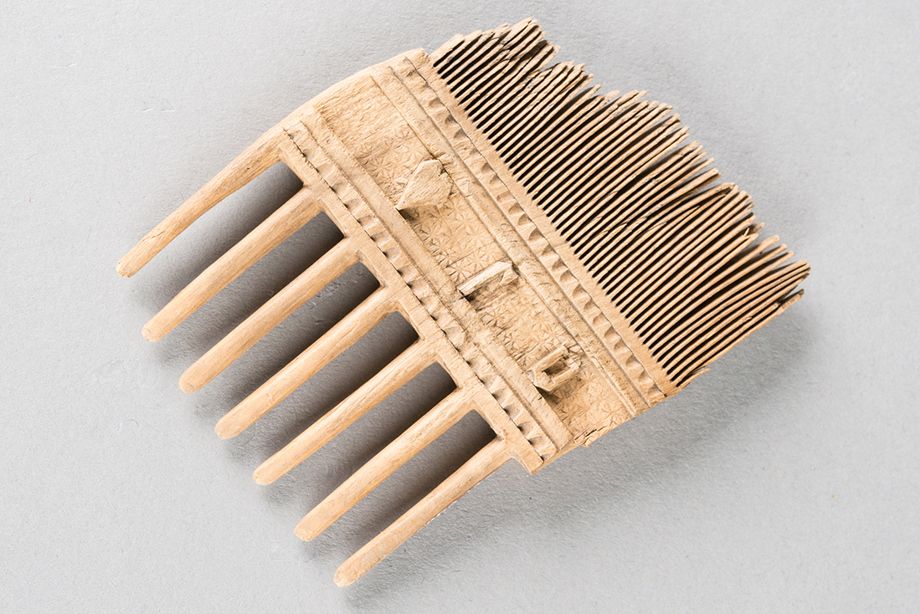

Watercolour drawing of a weaving comb, Nybster Broch, Caithness

From photographs, we can tell that both Beveridge and Nicolson attended the same excavation at Nybster led by Sir Francis Tress Barry.

This watercolour by Nicolson pays close attention to detail, much like Beveridge’s photographs of small finds. It shows a small bone weaving comb from Nybster Broch that would have been used in textile working. The elaborate decoration on the body of the comb suggests it was of some importance to the user.

Watercolour drawing of three artefacts, Nybster Broch, Caithness

This watercolour by Nicolson shows three artefacts. A bone pin (left) which would have been used for fastening clothes together and a piece of antler (right). The third object (bottom) is a ceramic crucible that would have been used for metalworking.

Nicolson’s drawings of the structures and objects uncovered during excavations with Sir Francis Tress Barry were often the only record, making them very important to our understanding of Caithness archaeology and history.

Digital Documentation

The Digital Documentation Team’s work feeds directly into the care of our sites and collections. Cutting edge digital technologies are used to document our heritage in 3D.

Not all of our collections are easy to access. Some are stored in remote locations, or are heavy, fragile or even unsafe. By making 3D records of the collection available through websites and apps such as Sketchfab, we can enrich people’s knowledge of Scotland’s history and conserve them for the future.

Thanks to 3D modelling (which means 3D printing is also possible), both researchers and the public can get a close up look at the intricate detail of historic objects.

Comb, Caerlaverock Castle, Dumfries and Galloway

Digital Documentation (including 3D scanning and photogrammetry, also known as ‘structure from motion’) is a way we can record historic objects, sites and landscapes without damaging or moving them from their original context.

This scan has recorded a double-sided birch wood comb made in the 1400s from Caerlaverock Castle, that can be assessed and inspected virtually. It allows us to examine its details like the fine teeth that were probably used for removing nits.

High Street, Ceres, Cupar

Ephemera (things that exist or are used for only a short time) like posters or graffiti can also document aspects of history that might otherwise disappear. This alternative type of archaeology can enrich our understanding of past everyday life.

This photograph captures the old village weigh-house at Ceres, covered in posters advertising local entertainment. It was also used as the burgh prison and the set of 'jougs' (Scots) on the right were used to punish minor offences, like drunkenness or swearing.

Sailor with astrolabe from Sailor's Loft, St Mary's Parish Church, Marketgate, Crail

This painted panel was originally within the Mariners' Loft in St Mary’s Church. It depicts a sailor using an astrolabe (a tool used by mariners to navigate the seas using the position of stars).

We do not know who painted it, but Beveridge thought it interesting enough to publish in his book ‘The churchyard memorials of Crail’ where he noted it had been found 5 years before, face down, as part of the church's floor.

Agents of Change at Pollphail, Argyll

These images were taken as part of a HES project dedicated to recording graffiti around Scotland, capturing fleeting moments of creative activity.

The abandoned village of Pollphail was constructed in the 1970s to provide housing for an oil platform that never materialised. Uninhabited till its demolition in 2016, the owners of this site invited graffiti artists to create works in the ruined village in 2009. The art collective Agents of Change staged their intervention with limited publicity or interpretation, leaving the works to be discovered by word of mouth and adding a new layer to the village's unique story.

Mill wall at Scalan, Aberdeenshire

This photograph records written graffiti documenting life in a 19th century farm and Catholic seminary in the Cairngorms.

Much of the traditional written history of Scalan is told through the lens of the seminary, but the stories told with the recorded graffiti give an insight into life on the farm and provide a rich social history. They detail severe winters, work life, personal stories and even list names of employees called up to war.

Detail of Norse Dragon (The Lion) carving in Maeshowe, Orkney

Maeshowe is one of the most impressive chambered cairns in Scotland. It was opened in 1861,but found empty as it had been entered by Norsemen long before.

This photograph captures one of the many Norse runic inscriptions and sketches carved into the walls of the main chamber. The ‘dragon’ or lion motif gives evidence to the norsemen's presence in the cairn, but is also a fine example of late Viking Age northern art.

Continue the exhibition

Find out more about Relics, Ruins and Ways of Life.